Recent discoveries show us that practically everything we think we know about the science of taste is wrong, wrong, wrong.

. . . by Bruce Feiler, from Gourmet, July 2008

Having just told you how I learned about the different taste receptors in the mouth (and tongue) at my first wine tasting class back in the late 1970’s, and how they affect my perception of wine taste, I ran across this article in a 2008 Gourmet article, which completely counters most of what I learned. (I’m still trying to go through a stack of magazines collecting dust in my family room.) All of this post comes from Bruce Feiler’s article.

So why this change? The human genome. But, of course. Scientists are only now discovering new information about us humans. Off the head of a pin. Hard to comprehend. And what they’ve found is that flavor chemistry is all over. It’s about how those chemicals interact with our bodies – like the fact that one person likes the taste of cilantro, for instance, and other people think it tastes like soap.

Up until recently all the food scientists worked on two basic truths: (1) there are four basic tastes – bitter, sweet, sour and salt (and they added umami later); and (2) different tastes are detected on different parts of the tongue – the “taste map,” they called it. I wrote up a previous post about those tastes. What they’ve determined is that we taste everything, everywhere in our mouths. And scientists are debunking #1 above too.

Mr. Feiler talked with biochemists, geneticists, sensory specialists and food psychologists. Consumers (like us) use the words flavor and taste interchangeably. Scientists do not. What’s important is that the tongue and mouth, assisted by the nose, are considered the body’s primary defense against poison. Ah. The human body tastes faster than it can touching, seeing or hearing – yes, we detect taste in as little as 1.5 thousands of a second, compared with 2.4 thousandths for touch, and 1.3 hundredths of a second for hearing and vision.

To be tasted a chemical must be dissolved in saliva and come in contact with tiny receptors that are grouped together in buds (taste buds, right?). They’re not just on the tongue but all over the inside of our mouths. They convert the chemical into a nerve impulse, which gets transmitted to the brain. Apparently the number of taste receptors we have has yet to be determined. Terry Acree of Cornell says it will likely be around 40 – a fixed number. Olfaction receptors, on the other hand, is much higher, around 300.

Now here’s some chemistry stuff – or the biological part – molecular biology has allowed scientists to identify which proteins, in which receptors, send which signals to the brain. Only one receptor can identify sweet . . . but more than 20 receptors detect tastes that are bitter. Because scientists are identifying the chain of messages (receptors to the brain) they can begin to manipulate the “conversation.”

When I first read this I thought, uh-oh. We’re going to start doing unnatural things to food (well, yes, they are). It’s not exactly like genetically modifying corn (see my essay about Monsanto if you’re interested), but it’s not too far off. What Feiler did was participate in a taste test of tomato juice. He drank 4 types: (1) V-8 juice with 480 milligrams of sodium; (2) low-sodium V-8 (doubling the amount of potassium chloride, thereby cutting the amount of sodium by about two-thirds); (3) and (4) were tomato juices containing low-sodium V-8 mixed with different amounts of Betra (something that is designed to block the unpleasant aftertaste of potassium chloride). Betra is a new substance made by Redpoint Bio, a very small company in New Jersey (located in an area called the Flavor Corridor). Betra therefore, blocks that taste of potassium chloride, which is fairy awful IMHO. So I like the thought of blocking that taste, but I wonder about what that will do to our bodies over time.

The bottom line is that we all taste things differently. So suppose I serve a French, succulent long-slow-baked beef pot roast to a group of friends. If you went around the table and asked them to be brutally frank, I’d probably hear mostly good remarks, hopefully because it was prepared well. Maybe I’d hear some raves about it. But there would likely be a couple of people who would say something negative – or maybe just “it was okay,” or didn’t have much flavor. Or even, “I don’t like beef.” We’re not talking texture here, but flavor. So even though we all have the same number of receptors, how the brain interprets what those receptors transmit can be very different (even among family members).

Did you know there are people referred to as “supertasters?” They experience almost all taste with more intensity – sugar is more sweet, Brussels sprouts more bitter, chiles hotter. Supertasters happen to also dislike plants with higher degrees of toxicity.

Now you throw into the equation culture. And they’ve identified – so far – about a dozen haplotypes (collections of persistent mutations within a particular population). How that plays out is, for instance, with lactose intolerance. Many African and Asian peoples can’t produce the enzyme lactase, which breaks down sugars in milk. Yet lactose intolerance is almost unheard of in European populations – people with traditions of herding and milking.

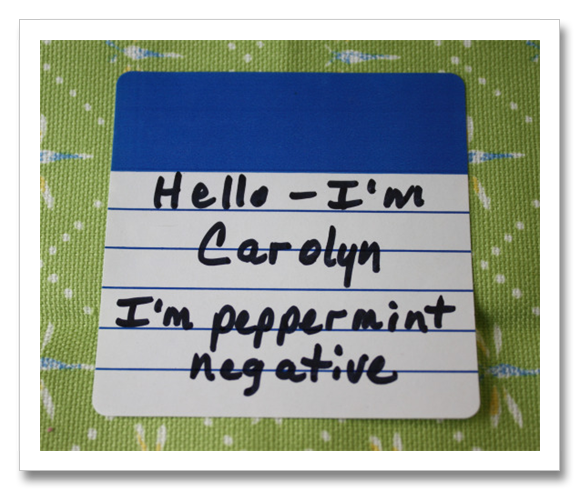

Where this leads us is that eventually every one of us will have our own food type (like a blood type). Hence the photos throughout the Gourmet article of people’s name tags – they said things like Joe – I am pumpernickel negative (meaning he can’t stand to eat it); or Stephanie – I am broccoli positive (meaning she adores it, I suppose); and lastly Frank – I am truffle negative.

Food companies are scrambling to find additives (see, this is where I don’t like the sound of this) that might improve or block particular flavors. Guess who’s paying for the research? Nestle, Coca-Cola and Campbell Soup. They want to know how to enhance the taste of sugar or salt in their packaged foods. For products that would trick the taste receptors into perceiving ingredients that aren’t there. Like sugar (expensive, and not so good for us) and salt (definitely not very good for us in the quantities most food processors use). And because the amount of this additive would be so small it could be listed on the label as “artificial flavors,” and the label wouldn’t tell you that it contains these bio-products. That part worries me a lot.

So how did the author do on the tomato juice taste test? He knew right away which one was the full-sodium V-8. The 2nd one with potassium chloride had a tinny, artificial taste, he thought (I agree, and I don’t buy it; I don’t buy V-8 either because of the high sodium). The other two, containing the bitter-flavor blocker, tasted more satisfying. The scientists can even figure out in the laboratory exactly how we’re going to like products containing these blockers. No taste tests needed – they do it all with test tubes and droplets of things.

The proponents of this (including many famous chefs like Ferran Adria at El Bulli in Spain and Heston Blumenthal of The Fat Duck near London) use chemistry and biology all the time in their chef-ing. At the London restaurant Blumenthal serves beet jelly and bacon and egg ice cream. He’s really into savory ice creams and sugar is a vital ingredient. So if the scientists have their way, the sugar would BE there, but they’d put in a sugar-blocker so we wouldn’t TASTE the sugar. Hocus-pocus, with chemistry. I’m just not convinced we should be doing this.

At the end of the article they included a short explanation about the human genome project:

Humans are 99.9% identical to one another – and to the archetype mapped and sequenced by the international Human Genome Projects (which had nothing to do with genetic engineering). The nucleus of each cell in our bodies (except mature red blood cells) contains the entire genome, and the genome’s DNA (composed of 3 billion chemical components) is arranged in 23 pairs of chromosomes, which in turn contain 20,000 to 25,000 genes. Genes only comprise about 2% of the genome; the rest serves other functions, including regulating the production of proteins, the molecules that perform most of the work of the cell. By isolating each taste receptor of the human genome, scientists can now begin to see how they react to every flavor known to humankind.

– – – – – – – – – –

And, I do happen to be peppermint negative. Almost makes me sick to my stomach. No red and white striped candy canes for me! Or mint chocolate ice cream either. And I’m mostly liver negative too – except duck liver (foix gras).

Recipes, from my archives, having nothing whatsoever to do with genomes or genes, or flavor-blockers:

A year ago today: Steak (beer marinated) with creamy peppercorn sauce

Two years ago today: Mace Cake

Leave a Comment!